The Spark of Inspiration

The journey into the fascinating world of algorithm design often begins with a spark, an encounter with a mind that not only solved problems but also illuminated the very nature of computation. For many, including the author of this reflection, that initial inspiration came from the profound work of Edsger Wybe Dijkstra during undergraduate studies. The revelation of his shortest path algorithm, coupled with the captivating story of its inception, served as a pivotal moment, transforming a general affinity for mathematics into a deep and abiding passion for the elegant art of algorithm design.

The anecdote of Dijkstra conceiving this foundational algorithm in a mere twenty minutes while enjoying coffee with his fiancée is particularly striking. This seemingly effortless creation of a solution to a problem with significant practical implications highlights the potential for profound intellectual breakthroughs that can arise from deep understanding and focused thought.

For a student grappling with the complexities of algorithms, this story offers a powerful message: that elegance and efficiency can emerge from clarity of thought, almost as an intuitive leap. This early exposure acted as a powerful catalyst, demonstrating how mathematical principles could be applied to solve real-world challenges in a remarkably efficient and elegant manner, thus solidifying a nascent love for mathematics into a specific and enduring fascination with the design of algorithms.

Intellectual Journey

Edsger Wybe Dijkstra's intellectual journey was shaped by a rich academic and familial environment. Born in Rotterdam, Netherlands, in 1930, he was the son of a chemist father who held a prominent position as president of the Dutch Chemical Society, and a mathematician mother. His mother's influence on his approach to mathematics, particularly her emphasis on elegance, proved to be a lasting guiding principle throughout his career.

Dijkstra during his early days of computing

Initially intending to pursue theoretical physics after graduating from high school in 1948 and studying mathematics and physics at Leiden University, Dijkstra's path took a significant turn when he began programming at the Mathematical Center in Amsterdam. It was here that he realized the intellectual challenges presented by programming surpassed even those of theoretical physics.

A telling anecdote from this period illustrates the nascent stage of computer science: when Dijkstra married Maria Debets in 1957, the authorities objected to "programmer" as his profession, leading his marriage certificate to identify him as a theoretical physicist instead. This lack of formal recognition for programming as a profession at the time underscores the pioneering role Dijkstra would play in establishing it as a scientifically respectable discipline.

Inspired by Adriaan van Wijngaarden, Dijkstra dedicated himself to laying the mathematical and scientific foundations that would elevate programming to an intellectually rigorous pursuit. His academic career flourished, with significant tenures as a professor of mathematics at Eindhoven University of Technology and later as the Schlumberger Centennial Chair in Computer Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin.

His initial resistance to fully embracing programming, driven by a desire for scientific rigor, and his subsequent commitment to establishing programming as a respectable field reveal his deep intellectual integrity and his visionary goal of transforming it from a mere technical skill into a genuine scientific endeavor.

The Shortest Path to Immortality

One of Dijkstra's most enduring contributions is his elegant algorithm for finding the shortest path in a weighted graph. Conceived in 1956 while he was working as a programmer at the Mathematical Center in Amsterdam, the algorithm arose partly from the practical need to demonstrate the capabilities of the newly inaugurated ARMAC computer to an audience unfamiliar with the intricacies of computation.

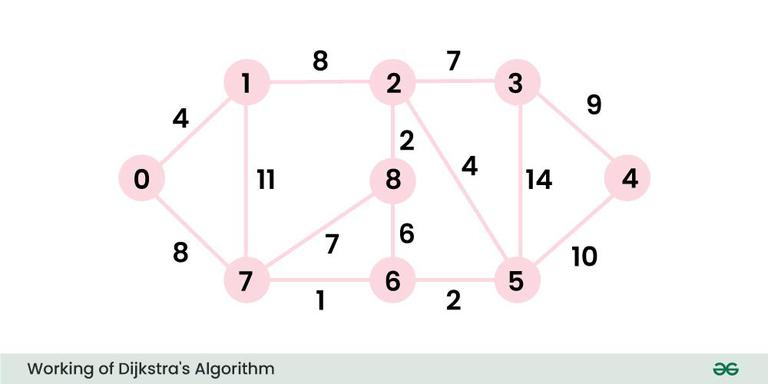

Visualization of the steps in Dijkstra's Algorithm

Dijkstra's Algorithm - Key Steps

The problem it solves – determining the shortest route between two points in a network where each connection has a specific cost or distance – has broad applicability, from mapping routes between cities to optimizing network traffic.

The fact that Dijkstra conceived this now-foundational algorithm in a remarkably short span of about twenty minutes, seemingly without the aid of paper and pencil, underscores the power of focused intellectual effort and a deep understanding of the problem.

Today, Dijkstra's algorithm remains a cornerstone of computer science, finding widespread use in countless applications, including GPS navigation systems, internet routing protocols, and even pathfinding in artificial intelligence for robotics and video games. It is applicable to both directed and undirected graphs as long as the edge weights are non-negative.

While other algorithms like Bellman-Ford can handle negative edge weights and A* uses heuristics to optimize the search towards a goal, Dijkstra's algorithm remains a fundamental and efficient solution for many shortest path problems. The continued relevance and pervasive application of Dijkstra's algorithm decades after its invention attest to its fundamental nature and enduring impact on the field.

Programming as an Art and Science

Beyond his groundbreaking algorithm, Dijkstra held a profound vision of programming as a discipline demanding intellectual rigor, aesthetic elegance, and a comprehensive grasp of complexity. He strongly advocated for clarity and simplicity in code, famously cautioning against "clever tricks" that could obscure the underlying logic.

The intersection of art and science in programming

"Computer science is no more about computers than astronomy is about telescopes."

This quote encapsulates his belief that the essence of the field lies in abstract thought and the intellectual challenge of computation, rather than the specific tools used.

To illustrate different approaches to programming, Dijkstra drew an analogy between programming styles and the compositional methods of Mozart and Beethoven. He described the "Mozart" style as one where the programmer conceives the entire program in their mind before writing any code, aiming for a flawless and complete creation from the outset. In contrast, the "Beethoven" style involves a more iterative and evolutionary process of writing, experimenting, and revising the code multiple times until the desired outcome is achieved.

His emphasis on simplicity and clarity in programming stemmed from a deep awareness of the cognitive limitations of programmers, famously stating that a competent programmer is "fully aware of the strictly limited size of his own skull". This underscores his belief that software should be designed to be easily understood and maintained by humans, not just efficiently executed by machines.

The comparison of computer science to astronomy emphasizes that the discipline's core is in the abstract realm of thought and problem-solving, elevating it beyond the mere mechanics of computers.

Skepticism Toward Natural Language Programming

Dijkstra harbored a strong skepticism towards the notion of natural language programming. He argued that natural languages, such as English, are inherently ambiguous and lack the precision necessary for instructing computers. In his view, formal symbolism provides the essential conciseness and lack of ambiguity required for effective communication in complex computational systems.

He famously expressed concern that natural language programming would simply make it easier to create programs whose flaws would be harder to detect, quipping that it would facilitate "making statements the nonsense of which is not obvious".

Dijkstra believed that the very "naturalness" of our native tongues allows us to easily make statements that are nonsensical without immediately realizing it. He drew upon historical examples from mathematics, such as the stagnation of Greek mathematics due to its reliance on verbal and pictorial methods, to illustrate how the absence of formal symbolism can impede intellectual progress.

Furthermore, he observed a decline in people's mastery of their own language, a phenomenon he termed "The New Illiteracy," which he saw as a further reason to be wary of natural language programming. Dijkstra viewed the requirement to use formal symbols in programming not as an inconvenience but as a valuable discipline that enables clarity and precision, allowing even those without exceptional genius to achieve complex tasks reliably.

His prediction that machines programmable in natural languages would be as difficult to build as they would be to use highlighted his profound understanding of the challenges involved in bridging the gap between the inherent imprecision of human language and the deterministic nature of computation.

On Machine Intelligence

"The question of whether computers can think is like the question of whether submarines can swim."

This famous analogy suggests that Dijkstra considered the question itself to be fundamentally flawed or at least a distraction from the more pertinent aspects of computation. Instead of focusing on whether machines could replicate human-like thought, Dijkstra emphasized the unprecedented intellectual challenge that computers present to humanity.

He believed that the most profound influence of computers would not be as mere tools but as catalysts for intellectual growth and the development of new modes of thinking. For Dijkstra, computing science was fundamentally about conceiving abstract mechanisms and effectively managing the inherent complexity of our own creations, rather than simply being about the physical machines themselves.

His analogy of submarines and swimming effectively redirects the focus from a potentially ill-defined philosophical debate to the more concrete and impactful reality of the intellectual demands and opportunities presented by computation. He recognized that engaging with the complexities of computation requires a new level of abstract thinking and problem-solving, which will have a far more profound and lasting impact on human civilization than simply using computers for automation or calculation.

Relevance to Modern AI

Dijkstra's insights continue to resonate deeply in the age of sophisticated artificial intelligence systems, particularly with the rise of Large Language Models (LLMs). His strong reservations about natural language programming echo in the ongoing discussions about the limitations and potential pitfalls of relying solely on natural language for interacting with and even programming AI.

Large Language Models representing the evolution of AI systems

While LLMs have demonstrated remarkable advancements in understanding and generating human language, they still grapple with issues of precision and can produce outputs that, while sounding coherent, may be factually incorrect or nonsensical. This aligns with Dijkstra's concern that natural language's inherent ambiguity makes it unsuitable for tasks requiring deterministic accuracy.

Interestingly, there is a growing movement within the AI research community to combine formal methods, which Dijkstra championed for software development, with AI techniques to enhance the reliability and trustworthiness of AI systems. This suggests a potential convergence with Dijkstra's emphasis on mathematical rigor as a foundation for reliable and correct systems.

The ongoing debate about whether the impressive predictive capabilities of LLMs constitute genuine intelligence or if they are merely sophisticated pattern-matching systems also reflects Dijkstra's perspective on machine intelligence. His analogy of submarines not truly "swimming" might suggest that he would view the current abilities of LLMs as remarkable achievements in prediction and generation, but not necessarily as evidence of true understanding or consciousness in the human sense.

The challenges of ambiguity in natural language, the need for precision in complex tasks, and the potential for generating plausible but incorrect information are all points Dijkstra raised decades ago that remain highly relevant to the current state of AI. The increasing efforts to integrate formal methods with AI indicate a recognition of the need for more reliable and verifiable AI, potentially through approaches that Dijkstra himself advocated.

Comparing Scientific Perspectives

To gain a broader perspective on the nature of intelligence, it is insightful to consider the thoughts of other scientific luminaries. Henri Poincaré, a towering figure in mathematics, emphasized the crucial role of intuition in mathematical discovery, stating, "It is by logic that we prove, but by intuition that we discover".

This resonates with Dijkstra's "Mozart" style of programming, where a deep understanding and intuitive grasp of the problem seem to precede the formal act of writing code. Both perspectives suggest that while logic and rigor are essential for validation and correctness, intuition and creative insight play a vital role in the initial stages of problem-solving in both mathematics and computer science.

In contrast, Geoffrey Hinton, a pioneer in artificial intelligence, has recently argued that human thinking is primarily based on analogy and resonance rather than pure logic.

This view potentially contrasts with Dijkstra's strong emphasis on formal logic and rigor in programming. If human intelligence operates more through pattern matching and drawing analogies, it raises questions about whether the pursuit of purely logical AI aligns with the fundamental nature of human thought.

The current capabilities of AI systems like LLMs, which excel at prediction by recognizing patterns in vast datasets, might be seen as aligning more with Hinton's view of analogy-based thinking than with Dijkstra's emphasis on formal, logical structures. This leads to the question of whether this predictive ability constitutes genuine understanding or intelligence in the human sense.

The Enduring Legacy

In conclusion, Edsger Wybe Dijkstra left an indelible mark on the fields of computer science and mathematics. His work, from the elegant shortest path algorithm to his profound insights on programming as an art and science, continues to inspire generations of thinkers. His emphasis on rigor, elegance, and simplicity remains a guiding principle for those who strive to master the complexities of computation.

Dijkstra in his later years, continuing to influence computer science

His critical perspective on natural language programming and his thought-provoking analogy on machine intelligence offer valuable frameworks for understanding the capabilities and limitations of modern AI systems. Dijkstra's legacy extends beyond specific technical contributions to a broader philosophy of approaching computation with intellectual discipline and a deep appreciation for fundamental principles.

His critical and often outspoken nature, while sometimes controversial, ultimately stemmed from his unwavering commitment to elevating the field of computer science towards greater rigor and maturity.

The enduring inspiration derived from his work continues to shape the thinking of computer scientists and reminds us that the pursuit of elegance and rigor is not a dispensable luxury but a crucial aspect of creating robust and meaningful computational systems.